Another week, another night in Las Vegas – err, I mean, the J’Ordain Casino… If any of my players are reading this, stop here, as I do kind of get into some potential future tangents in the post below, so spoilers abound! Don’t ruin it for yourself, okay? Other warnings for the general public include mentions of prostitution, drugs, and gambling.

Anyway, now that our group has gotten their feet wet, the game has opened up to full sandbox play! From here on out, I’m along for the ride, and am mostly just improvising based on hex keys and loose mini adventure ideas. I ran a few iterations of Sectors Without Number, added in the places the group had visited in areas they made sense, and then created a cute little mouseover hex map in Foundry. To finish it off, I did some drawing up of the three main factions – we have the Space Mafia (I need a better name), the Interstellar Influence Navy (the galaxy-wide ‘space police’), both of whom will remain on the hexes they’ve been placed on until interacted with, and the courier company that Blanche and Hermes used to work with (I’ll randomise their potential encounter location every session). There are also the space whales, which move around the hex map as the players do (I roll for them), and are mostly there just for fun. Rare that they actually manage to make it to a system – rarer still that the party will interact with them. But just knowing they exist fills me with joy, so I don’t mind if the two groups never meet.

The session started with some housekeeping (they decided to name their ship the Joint Enterprise), picking their next destination (I didn’t even need to list off the other potential hexes, the players just really, really wanted to get shitfaced and gamble at the casino station), and then the weekly audio transmission log. These audio transmission logs will contain news bulletins, direct messages, etc., and happen every spike drive drill the group takes (so, first thing every session, roughly). Depending on who is staffing the communications area, they’ll also have access to their personal emails from their dataslabs/compads. Caitlin was manning the comms station today, and listened to two direct messages from Basil (“Hi. i’m going surgery few days. thanks support.” and “p.s. guys rescue is ok, paying for”) as well as a few ‘spam’ messages: from Geico insurance regarding their spike drive, some lottery winnings that the group definitely didn’t enter, and a reminder on student loans payments that Caitlin opted to skip through.

Funny thing, the Geico insurance notice is actually legitimate. In two more jumps, and after two more warning notices, their tier 1 spike drive will fail. If the group actually listens to the message, they’ll find out that they can get it swapped out for free, or a potential upgrade for 50% off. The group has enough money to pay for a replacement outright, so even if they continue to ignore the warning, they’ll survive – but it will put an awful dent in their funds. They may even potentially upgrade their drive before then, totally unaware of the discount offer… On the other hand, taking up the replacement offer comes with other problems: if you recall, the group swapped the ship’s identification in order to go off the radar, and is currently not recognisable by the courier company. But if the group takes up the insurance offer, the courier company it originally belonged to will get pinged, alerting them to perhaps something fishy going on – beyond just a potentially dead pilot and blasted ship!

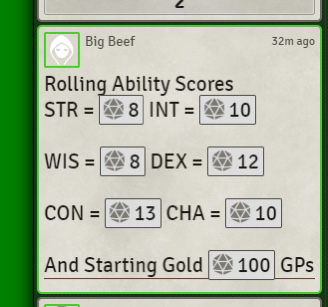

But we’ll burn that bridge when we get to it. After spending several days in metaspace, the crew arrives at the J’Ordain Casino, a buzzing space station locale of drinks, drugs, and sexual freedom. There are flight crews spelling out dazzling advertisements, laser beams, thick clouds of cigarette smoke flooding the halls, and a race course around the station for ships to make use of (more on that later). Prep-wise, I pulled a few gambling card-games-turned-dice-games from the internet and kept them on hand (blackjack and poker) and drafted up a little 3d6 slot machine mechanic in a few minutes so the group could do any of those if they liked. Pillboi and Blanche opted to play a few rounds of Poker – Blanche losing terribly and borrowing credits from Pillboi, who was trying to sell drugs on the sly to the rest of the tables. At the end of it all, the two headed off to the bar and came out 100 credits richer each (though how much of Blanche’s money was actually Pillboi’s is up for debate). Caitlin wanted to schmooze up some rich folk, and went straight to the bar area – grabbing the business card of a big beautiful drug-smoking woman named Clarice, who has been spearheading a longtime industrial project a few systems out creating a gigantic solar array. Caitlin convinced her to exchange contact information and gained a new potential big client for their future drug enterprise once they get their hands on the psychoactive plant in Terra Purr’ma. Caitlin also offered her body for sale, and spent a few hours with the woman (but unfortunately ended up breaking even after needing to pay for Clarice’s drycleaning due to a wine-spilling incident). Hermes, meanwhile, scoped out the place for some money-making opportunities… he had worked on the slot machines before, and knew how they worked, but preferred to try counting cards at the blackjack table (I improvised how that worked and I’m not sure I loved how I ran it, so I’ll probably revisit the idea later). The staff got suspicious after a while but not enough to want to do anything about it, and he slunk off to the bar after a while to meet Caitlin and the rest.

With the four of them enjoying some drinks alone in Clarice’s private booth (she left to take a call), an announcement played over the casino’s intercom system: the betting counter was now open for bets on the next ship race starting in a few hours. This race is interesting- the casino is hosting a few well-renowned ‘Formula 68’ racing pilots for the week, and one particular pilot, Pelkan Wales, is an almost guaranteed win (the house is expecting to pay out a fair amount of cash on this, but it’s worth it for the advertising and sponsorship money).

The four hatch a plan – they immediately want to rig the race, and manage to grab some pit uniforms for Hermes and Blanche to head down and mess with the ships. They don’t think they can make it so one person wins, but they do think that they can spread out their bets and just prevent Wales from winning. The first uniform they drugged a nearby employee and stole his outfit. For Blanche, they tried to grab a very sketchy, nervous catfolk’s uniform the same way but failed in trying to knock him out with a frying pan, and he slunk off (strangely, not alerting security of the incident…), but ended up just sneaking into the staff lockers to grab a set. The two of them (mostly) get away without suspicion while doing this, and thanks to some incredible rolls down at the shipyard, get to not only call attention to some much-needed repairs on one of the “worst drivers in the circuit” (Gioli Brusso)’s ship, but also sabotage Pelkan’s in such a way that he struggles to handle it. The race is on – Pelkan falls behind, and (I did roll for this), the worst driver in the circuit (thanks in part to the repairs on his ship), pulls ahead for the win with 13:1 odds, netting the party a 23000 credit profit on their bets (they spread them out across the other drivers). The group quickly decides to cut and run, just in case, and take off in their ship, ending the session.

Overall, the session was fine- a bit of a slow pace today, but most folks were tired and I honestly had a lot of fun regardless! I loved the characters I came up with (the racers, the pit staff, Clarice – all improvised but all have clear motivations and backgrounds). Though, I am never sure how actually-playing-gambling-games-with-dice feels during a session, but everyone seemed to like these ones fine so I think it worked out. I do think I ought to flesh out the factions a lot more by next session – I got away with it this time as they haven’t been interacted with yet, but I’ll need to get a clear grasp on their galactic game plan to help shepherd the players into potential meaningful antagonists and allies. I also fear that I’m not going to be able to obey the “law of conservation of NPCs”, so I’ll need to keep careful track of the names this session and figure out how I can incorporate them later.

So, what’s on the menu for next week? Well, Wales was suspected of driving under the influence due to the poor handling of his ship during the race – the next audio transmission logs will contain a few news stories about his ongoing DUI investigation and scandal (he actually was under the influence of both drugs and alcohol from the casino). This doesn’t directly impact the party, per see, but I think it may open up some opportunities for their drug dealing operation in yet-unknown ways. I’ll leave it to them to think about it. Also, that sketchy catfolk who didn’t alert security of the woman who literally tried to knock him out with a frying pan (and then played it off as a joke)? Well… who knows what happened with that, but during the chaos of the surprise win upset, the casino happened to be robbed, and over ten million credits are missing from their internal digital banking system. There’s a bounty out for those that have any information regarding the incident…